Maunakea, Hawaiʻi – Jupiter may be the bully planet of our solar system because it’s the most massive planet, but it’s actually a runt compared to many of the giant planets found around other stars.

These alien worlds, called super-Jupiters, weigh up to 13 times Jupiter’s mass. Astronomers have analyzed the composition of some of these monsters, but it has been difficult to study their atmospheres in detail because these gas giants get lost in the glare of their parent stars.

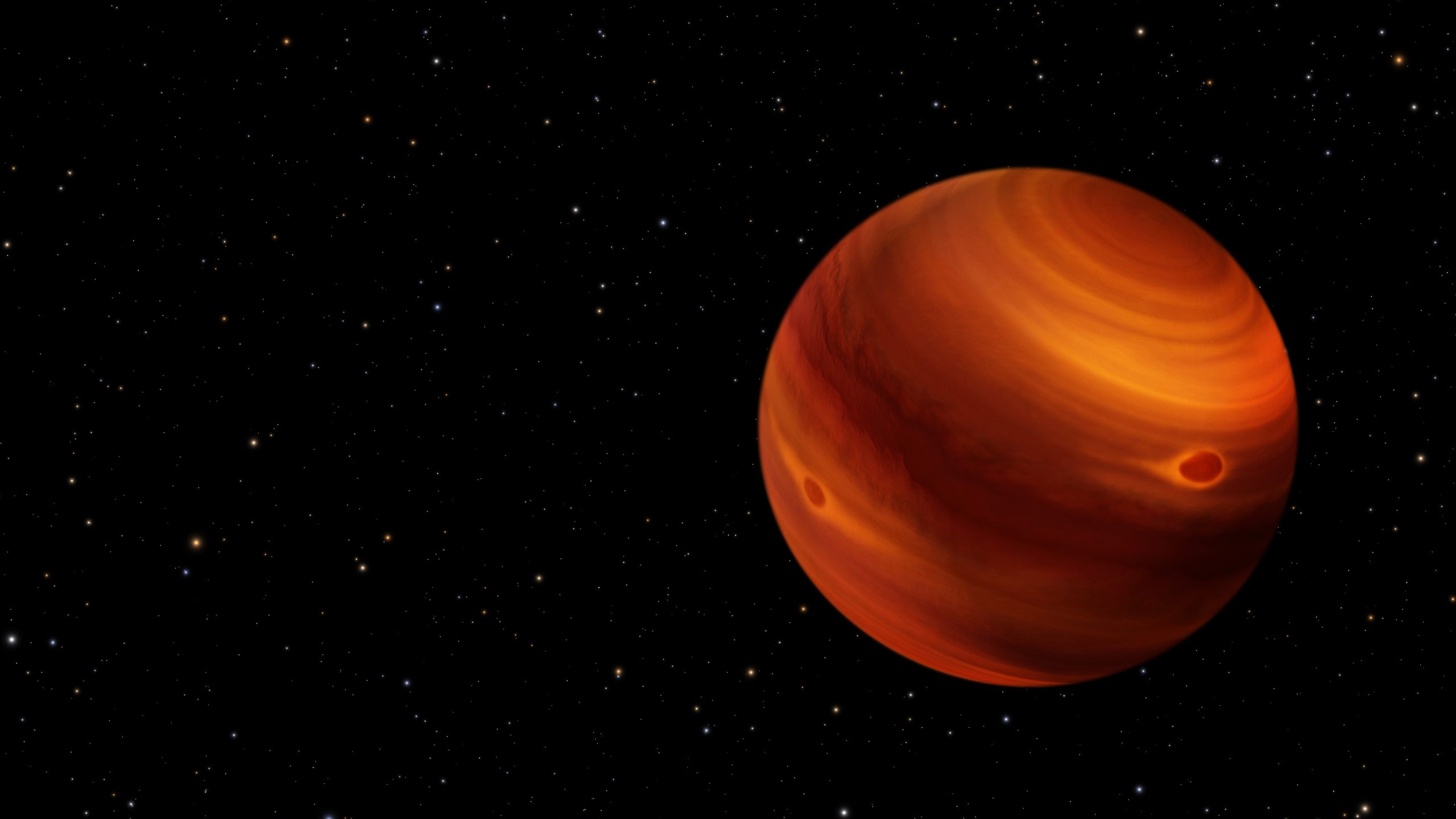

Researchers, however, have a substitute: the atmospheres of brown dwarfs, so-called failed stars that are up to 80 times Jupiter’s mass. These hefty objects form out of a collapsing cloud of gas, as stars do, but lack the mass to become hot enough to sustain nuclear fusion in their cores, which powers stars.

Instead, brown dwarfs share a kinship with super-Jupiters. Both types of objects have similar temperatures and are extremely massive. They also have complex, varied atmospheres. The only difference, astronomers think, is their pedigree. Super-Jupiters form around stars; brown dwarfs often form in isolation.

A team of astronomers, led by Elena Manjavacas of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, has tested a new way to peer through the cloud layers of these nomadic objects. The researchers used an instrument at W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea in Hawaiʻi to study in near-infrared light the colors and brightness variations of the layer-cake cloud structure in the nearby, free-floating brown dwarf known as 2MASS J22081363+2921215.

The Keck Observatory instrument, called the Multi-Object Spectrograph for Infrared Exploration (MOSFIRE), also analyzed the spectral fingerprints of various chemical elements contained in the clouds and how they change with time. This is the first time astronomers have used MOSFIRE in this type of study.

These measurements offered Manjavacas a holistic view of the brown dwarf’s atmospheric clouds, providing more detail than previous observations of this object. Pioneered by Hubble observations, this technique is difficult for ground-based telescopes to do because of contamination from Earth’s atmosphere, which absorbs certain infrared wavelengths. This absorption rate changes due to the weather.

“The only way to do this from the ground is by using Keck’s high-resolution MOSFIRE instrument because it allows us to observe multiple stars simultaneously with our brown dwarf,” said Manjavacas, a former staff astronomer at Keck Observatory and the lead author of the study. “This allows us to correct for the contamination introduced by the Earth’s atmosphere and measure the true signal from the brown dwarf with good precision. So, these observations are a proof-of-concept that MOSFIRE can do these types of studies of brown dwarf atmospheres.”

She decided to study this particular brown dwarf because it is very young and therefore extremely bright. It has not cooled off yet. Its mass and temperature are similar to those of the nearby giant exoplanet Beta Pictoris b, discovered in 2008 near-infrared images taken by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in northern Chile.

“We don’t have the ability yet with current technology to analyze in detail the atmosphere of Beta Pictoris b,” Manjavacas said. “So, we’re using our study of this brown dwarf’s atmosphere as a proxy to get an idea of what the exoplanet’s clouds might look like at different heights of its atmosphere.”

Both the brown dwarf and Beta Pictoris b are young, so they radiate heat strongly in the near-infrared. They are both members of a flock of stars and sub-stellar objects called the Beta Pictoris moving group, which shares the same origin and a common motion through space. The group, which is about 33 million years old, is the closest grouping of young stars to Earth. It is located roughly 115 light-years away.

While they’re cooler than bona fide stars, brown dwarfs are still extremely hot. The brown dwarf in Manjavacas’ study is a sizzling 2,780 degrees Fahrenheit (1,527 degrees Celsius).

The giant object is about 12 times heavier than Jupiter. As a young body, it is spinning incredibly fast, completing a rotation every 3.5 hours, compared to Jupiter’s 10-hour rotation period. So, clouds are whipping around the planet, creating a dynamic, turbulent atmosphere.

Keck Observatory’s MOSFIRE instrument stared at the brown dwarf for 2.5 hours, watching how the light filtering up through the atmosphere from the dwarf’s hot interior brightens and dims over time. Bright spots that appeared on the rotating object indicate regions where researchers can see deeper into the atmosphere, where it is hotter. Infrared wavelengths allow astronomers to peer deeper into the atmosphere. The observations suggest the brown dwarf has a mottled atmosphere with scattered clouds. If viewed close-up, the planet might resemble a carved Halloween pumpkin, with light escaping from the hot interior.

Its spectrum reveals clouds of hot sand grains and other exotic elements. Potassium iodide traces the object’s upper atmosphere, which also includes magnesium silicate clouds. Moving down in the atmosphere is a layer of sodium iodide and magnesium silicate clouds. The final layer consists of aluminum oxide clouds. The atmosphere’s total depth is 446 miles (718 kilometers). The elements detected represent a typical part of the composition of brown dwarf atmospheres, Manjavacas said.

She and her team used computer models of brown dwarf atmospheres to determine the location of the chemical compounds in each cloud layer.

The study will be published in The Astronomical Journal and is available in pre-print format on arXiv.org.

Manjavacas’ plan is to use Keck Observatory’s MOSFIRE to study other atmospheres of brown dwarfs and compare them to those of gas giants. Future telescopes such as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, an infrared observatory scheduled to launch later this year, will provide even more information about a brown dwarf’s atmosphere.

“JWST will give us the structure of the entire atmosphere, providing more coverage than any other telescope,” Manjavacas said.

She hopes that MOSFIRE can be used in tandem with JWST to sample a wide range of brown dwarfs and gain a better understanding of brown dwarfs and giant planets.

“Exoplanets are so much more diverse than what we see locally in the solar system,” said Keck Observatory Chief Scientist John O’Meara. “It’s work like this, and future work with Keck and JWST, that will give us a fuller picture of the diversity of planets orbiting other stars.”

ABOUT MOSFIRE

The Multi-Object Spectrograph for Infrared Exploration (MOSFIRE), gathers thousands of spectra from objects spanning a variety of distances, environments and physical conditions. What makes this large, vacuum-cryogenic instrument unique is its ability to select up to 46 individual objects in the field of view and then record the infrared spectrum of all 46 objects simultaneously. When a new field is selected, a robotic mechanism inside the vacuum chamber reconfigures the distribution of tiny slits in the focal plane in under six minutes. Eight years in the making with First Light in 2012, MOSFIRE’s early performance results range from the discovery of ultra-cool, nearby substellar mass objects, to the detection of oxygen in young galaxies only two billion years after the Big Bang. MOSFIRE was made possible by funding provided by the National Science Foundation.

ABOUT W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

The W. M. Keck Observatory telescopes are among the most scientifically productive on Earth. The two 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes atop Maunakea on the Island of Hawaiʻi feature a suite of advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs, high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectrometers, and world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems. Some of the data presented herein were obtained at Keck Observatory, which is a private 501(c) 3 non-profit organization operated as a scientific partnership among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors wish to recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this mountain.